More

Profit and profitability are two concepts which are often confused. But as appears from the foregoing, profit is not a measure of profitability. Assume that you have two savings accounts, in which you have saved €1,000 in one and €5,000 in the other. The first account pays interest of €50 and the second €100. The profit (the interest) in the latter account is twice the size and it would be easy to believe that the profitability is higher too. But if the profit is placed in relation to the amount saved, we see that the profitability is 2.5%, that is, only half as large compared with the first account -- which pays 5%.

In a similar fashion, we can look at the profitability in a company. If company A shows a profit of €200M and company B a profit of €400M, this does not necessarily mean that company B, with its higher profit, is more profitable. In order to measure profitability in a company, the profit must be placed in relationship to the capital which the company uses, i.e., the capital which is invested in the company.

We can thus define profitability in a company as:

Profitability=profit/invested capital.

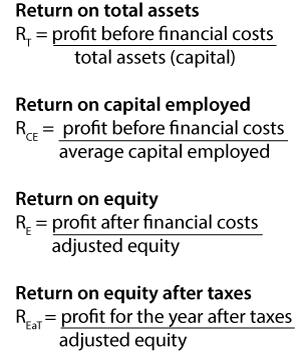

The profit in a company can be seen as the interest" on the capital which has been invested in the company. Sometimes the concept of return on capital is used as a synonym for profitability in a company. The different profitability measures used are:

The term "adjusted equity" capital (AEC) includes that part of the untaxed reserves which belongs to the company and the shareholders after taxes have been paid. In the calculation of the adjusted equity capital regard may also be taken to the average equity capital during the year. Therefore, AEC is usually higher than what is reported on the balance sheet as equity capital.

What, then, is sufficient profitability? The answer, of course, is it depends. In a simplified model of the pricing of capital, it is assumed that the market (lenders, investors, banks and so on) determine what profitability (return) they expect in order to offer capital. The profitability which the market expects determines in turn the price of capital. The interest rate which a bank wants in order to lend you money is thus the market price you have to pay to borrow money from the bank.

The market price of capital varies with the risk, mainly dependent on whether a borrower can re-pay the amount used. For example, in order to get access to capital loan and obtain the market price, you are expected to pay the required interest and amortization. In the same way, it is expected that a company will be able to pay interest and amortization to the bank as well as dividends to its owners.

Of course, the lower the risk that a borrower cannot make its payments to a lender, the lower the price of the loan will be. If there is no uncertainty at all, for instance when the state borrows, it is common to speak of a risk-free investment and a risk-free interest rate. Since the state is usually seen as a very safe payer, the interest rate on government bonds is often used as a measure of a risk-free interest rate. Loans to private persons and businesses therefore include a certain risk premium in addition to the risk-free interest rate.

The price of capital is, however, not only affected by the ability to re-pay capital. It is also affected by the market's willingness to take risk. In good, positive times, lenders and investors are willing to take greater risks and offer capital for lower compensation, and in uncertain times they are asking for a higher price.

How, then, is the market price of equity capital (the owners' capital) to be determined, that is, the capital which is often called risk capital? Basically, the price of equity capital is the return which an investor expects in order to be willing to put capital into a company or to buy shares on a securities exchange.

An investor's requirement as to the return on capital of her or his investments is the sum of risk-free interest plus a risk premium for the unavoidable, systematic business risk, that is, for the risk which cannot be eliminated through the use of a diversified investment portfolio. The size of the risk premium cannot be determined with certainty; it varies with the business, over time and is based to some extent on subjective expectations about the future. The risk is naturally greater with a newly started, unlisted company as compared with a large, listed company, the shares of which can be sold if the investor is not pleased with the developments in the company.

Example:

Assume that the risk-free interest rate, at a particular point in time, is 2%. Assume, further, that the average risk premium, at the same point in time, for large companies on a securities exchange is 5.6%. The total required return (and the price) for securities exchange listed ownership capital here will be 7.6%.

Since the business and financial risk in smaller companies is greater, the risk premium will be affected also. We will assume that a small listed company (e.g., market value less than €50 million) at the same point in time has a risk premium supplement of 3.7%. This gives a total risk premium of 9.3% and a required return of 11.3%.

In an equivalent way, investors will make judgments about risk premiums and return requirements for unlisted companies. It is not uncommon for an investor to require twice the risk premium in order to contribute capital to an unlisted smaller company, which would mean a total return requirement (and price) for equity capital in the company exceeding 20%. A contributing cause of the materially higher risk premium in this case is that the shares can be very difficult to sell (the shares are not liquid) if the investor is not pleased with the developments in the company.